Is Free Enterprise At Home More Important Than Free Trade Abroad?

Recently The Prickly Pear ran an article by Oren Cass called Free Trade’s Origin Myth. Then we ran a rejoinder entitled On Comparative Advantage and International Capital Mobility by Donald Boudreaux, a staunch defender of free trade.

As someone quite supportive of free markets, and free trade, we found reading both a bit disturbing.

Furthermore, it reminds me of an old joke. A lawyer, and doctor, and an economist were driving in a car, collided with another vehicle, and veered off into a very deep ditch. It soon became clear that getting out of this deep hole was going to be next to impossible. The doctor started checking the other passengers and was worried about the occupants of the other vehicle. The lawyer was concerned about liability and who was going to pay. After some time to ponder their predicament, the economist responded by declaring: “First, assume a ladder.”

At the outset, our preference would be to have robust free trade abroad and muscular free enterprise at home. However, that position does not adequately describe current circumstances.

It was not that Cass attacked free markets per se (free trade is very much part of the free market), but rather he argued that things just don’t operate in practice or history the way theory would like to suggest.

In some respects, the argument is similar to that about unrestricted illegal immigration. In theory, libertarians support the free movement of capital and people. But in practice when you run a welfare state as we do in America, and add extra incentives of cash bonuses, healthcare, and travel expenses, then you have a problem. In the 19th century and the early 20th, that was not the case. Milton Friedman famously said you cannot have unlimited immigration and a welfare state together.

Does one acknowledge real conditions or does one stick doggedly to theory, even if the the theory is valid?

What if the US were to immediately abolish all violations of the principle of free trade, but our major trading partners did not? How would that work out?

In truth, we don’t practice what we preach about free trade, and neither do our trading partners, but economists keep singing from the same hymnal as if all were practicing the same true religion.

One of the critiques of Donald Trump and the MAGA movement is that it tends toward the protectionist, has resisted globalization and that this would both cost the American consumer more and perhaps even lead to trade wars. Trump’s position offends many legacy Conservatives such as National Review, the Wall Street Journal, and the American Enterprise Institute. Our Libertarian friends often cite this problem as a sign of Trump’s illiberal instincts.

As usual in these kinds of conversations, it is important to define what one means by the term “free trade”. Free trade should mean commerce unrestricted by tariffs or other legal or illegal practices, allowing the principle of comparative advantage to work. Let those that can do it better and cheaper do it, and don’t prop up the inefficient.

Just as it may be more efficient to make autos in Alabama as opposed to Michigan, it may be even more efficient to make them in Mexico. The more efficient, the lower the prices for the consumers. The pain felt by communities in Michigan or Alabama is felt to be secondary to the principle of free trade, which while inflicting local pain, is better for everyone overall.

Not only is the pain and social disruption often ignored, but when a nation can no longer refine oil, bend metals, manufacture microchips, and make chemicals, it can’t fight a war. Therefore, certain important strategic supply lines may fall into the hands of adversaries. So, when one looks at all the trade-offs, maybe cheaper goods should not be the only consideration for policy.

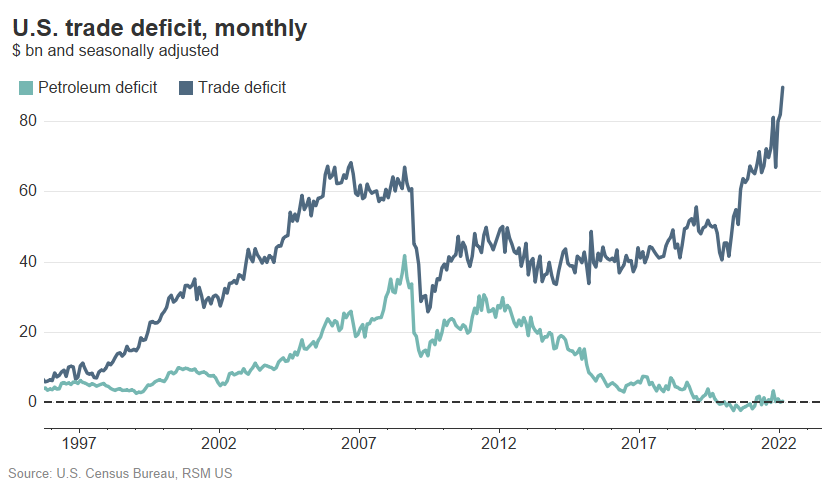

The US trade balance has been getting progressively worse and now we import about $900 billion worth of goods beyond what we sell abroad. Every month seems to break a new record. What improved for a while was the oil trade. Note we were roughly in balance just before the turn of the century.

During COVID-19, we discovered how many important supply chains, from antibiotics to microchips, are dominated by China, a country hostile to US interests. Violation of economic theory may cost some money. Violations of sound defense theory can get you killed or subjugated. How would you trade those two things off?

Moreover, it should be pointed out that the US grew and prospered for many years, with little or no inflation, with tariffs being the main source of Federal Revenue. Free international trade seems to be less important than free markets at home, or that could not have been the case.

To help the market flourish, we need secure property rights and the rule of law. They also flourish with limited regulation and low taxation. We generally had that in an earlier era, even during a time of complex tariffs.

So you could say that Trump did a relatively poor job on trade, but a relatively good job on taxes and regulation. If so, he is not so much “anti-free trade” as he was a throwback to an earlier Republicanism. More likely, he saw the trade issue as a realist, not an economic theorist.

But we would argue that we don’t have “free trade” in the sense you would use the term for teaching purposes in economics class. Just a casual perusal of the WTO website should reveal how complicated our system of “free trade” really is. Not only are tariffs negotiated among countries, but there is significant international agency bureaucracy involved, including the UN, an organization that shouldn’t be trusted with any task.

Not only are their differential tariffs applied among countries and goods, but nations can also change the game by giving below-market loans to certain industries (we have our Export-Import Bank), outright subsidies, anti-trust protection, and widely varying regulatory environments can create different production costs quite independent of tariffs. Also, some countries like Japan are known for “nontariff barriers”, such as lengthy safety or quality inspections. If your shipment is held up on the docks for six months, they obviously might be more “expensive” than those that don’t get delayed.

Genuine free trade would not require any of this complexity. If free trade simply means one country trades with another without tariffs or other trade barriers, who needs an army of lawyers, diplomats, economists, and bureaucrats? But in reality, we have them.

Some have argued that if one nation wishes to reduce its wealth (lose money on production), just to sell us cheaper goods, then we are the winner and they are the loser. But if their actions hollow out most of our domestic production, what happens if that country that subsidized our consumers at one point in time, now in the absence of competition, wants to raise prices drastically? More importantly, what if a country (like China), subsidizes its industries to the detriment of its internal consumers, to gain dominance in important industries, and then becomes an active military adversary?

The current rush to re-shore certain industries is illustrative of this point. Both to restore competition or national security, it can take years and significant expense to rebuild once destroyed industries if it can be done at all. Was it worth the temporary period of cheap goods?

Some also argue an accounting-like argument. The US buys goods from foreigners. We get the goods, and they get our money, which is mostly redeposited or invested in our capital markets. It is an accounting balance and there is no harm, no foul. However, if one loses say a major industry important for defense, and we buy what we need from foreigners, they deposit the money in our financial markets. However, that capital can leave our system in a nanosecond but reconstructing our defense base may take a decade. Moreover, what if the nation supplying us decides it needs the productive facilities for its own defense, or ironically, to fight us, what happens? How long will it take to find alternative suppliers elsewhere?

Even if it does not involve a strategic industry, we may lose an important industry permanently in trade for capital that may be quite temporary. Then how do the accounting books look? Does it look different over time?

Besides, what is a “strategic” industry? On the surface, things like steel look strategic. But knowledge and training are strategic. You can’t make steel without it. Making steel is complicated let alone making missiles. When you break it down, multiple industries are engaged just to make a pencil. Pharmaceuticals on the surface do not look strategic, but if you get wounded in battle suddenly they are. Since the industry is so integrated, it is hard to sort out what is truly strategic and what is not. Many consumer and military items can have dual-use functions, like making footwear or having heavy trucks.

And if you offer protection for “strategic industries”, you can bet lobbyists will soon be at work to be sure the industry they represent is now regarded as “strategic”.

In reality, what we evolved to is managed trade. This is a regime of various trade agreements (don’t need them in genuine free trade) that come out of the messy political blender of special interests that in turn funds politicians in a never-ending self-serving cycle. This same process exists in many other countries that suffer from the same problems.

To our Libertarian friends, please, let’s not dignify this process as “free trade”, and then make theoretical criticisms of Donald Trump. Don’t “assume” a ladder. It would be fairer to say we practice “managed trade”, and so does everyone else, and he simply wants to manage things more to America’s advantage than to manage for the “international community”.

The US is certainly not alone in this effort, or even the worst. China has been using subsidies, loans, and currency manipulations for years to drive a program of overt mercantilism. Yet many of our leaders have not only ignored these malpractices, they personally financially benefited from them by their own investments in China. In this process, it has hollowed out American jobs and capabilities so badly we can’t even produce enough artillery shells. If we had to fight a war, could we do so without Chinese imports?

As a result, whole skill sets to make things have been lost and industries/communities destroyed. Moreover, China has not been shy about stealing our intellectual property. Yet American politicians say they favor “free trade.” What a joke and they are defended by economists repeating a mantra and not looking at reality.

In the real world, Americans have to deal with a tone-deaf political class and stiff foreign competition. This is often done with their economic hands tied by an inferior educational system (run by the government), high taxes, stifling regulation (run by the government), and an immigration system that does not favor getting skilled immigrants. Environmental regulations are among the worst. US industry is tied in knots while China is given free rein by the arbitrary designation as “developing”, whatever that might mean.

Do you really want to call that “free trade” and then make elaborate arguments based on patently false suppositions?

Finally, we top the whole thing off with DEI, which puts people in positions in both corporations and government who did not get there through merit, hard work, and loyalty. Meanwhile, foreign competition can promote on merit and beat our brains out. It makes it kind of difficult to compete when you are tied up by your government that then makes sweetheart deals with foreign countries and calls it free trade.

We are all for foreign competition. It will keep us sharper. But with free enterprise at home, there should be sufficient competition to keep our companies in line.

We don’t have an easy answer to the problem. We can’t control what other countries do, but we sure could deregulate and cut taxes here at home. That will make us more competitive in any trading environment.

It would be nice if all our trading partners were like Denmark and there was a very low probability of armed conflict. But our sense is that will not be likely in the future and we can’t find much record of that in the past either. Free enterprise at home, low taxes and regulations, a sound educational system, and the rule of law, are likely more important than “free trade.” As mentioned before, the US did quite well when we had free enterprise at home and tariffs.

The theoretical free trade regime was hardly practiced in the past and it sure is not practiced in the present. If true, that reality needs to be acknowledged and then managed to the benefit of the American people.