How Sri Lanka’s Attempt at Modern Monetary Theory Went Horribly Sideways

Editors’ Note: One of the first major book reviews undertaken at the Prickly Pear, was a critical assessment of Modern Monetary Theory, which we found not really modern and hardly a theory. It is just a clever academic excuse for the old principle of the government paying for its expenses by printing excessive quantities of money, and depreciating the value thereof. It has happened many times in history, and why academics insist we repeat the mistake over and over again remains a mystery. However, inflationary policies should be more than just an academic debate. The destruction of the savings of millions of people is not only quite harmful to the people directly but very harmful to society and the political structure. It almost always results in significant social revolution, often ending in rebellion and violence. If the government is to be allowed the monopoly power to issue money, then government must issue honest money, that is money that holds its value over long periods of time and that is neutral in its social effects. It should not favor debtors over creditors, spenders over savers, and the rich over the poor. It should be as much as possible, a stable and neutral factor, allowing long-term contracts and long-term productive endeavors to be financed, without the incessant bursts of wild speculation that are a fundamental hallmark of inflationary policies. One of the glaring failures of both the Republican Party and the MAGA movement is that has not emphasized the critical role of honest money and sound government finance. The critical function of the government’s control of money needs to be elevated in our political priorities, or much of what we seek to change will simply disappear in an upheaval caused by destructive monetary management.

While many factors contributed to the crisis in Sri Lanka, a key one has been conveniently overlooked by many economists: the monetization of its debt.

Developments over the past few months in the small island nation of Sri Lanka have captured the attention, and concern, of many around the globe. Footage has gone viral on social media of protestors storming the President’s House and occupying the streets of the capital city of Colombo, prompting the nation’s government to declare a state of emergency.

The upheaval in Sri Lanka is largely the product of an economic crisis that’s seen a chronic shortage of key goods such as food, fuel, and medicine, leaving in its wake an inflation rate upwards of 70 percent. Mainstream economists’ fingers have pointed to a variety of explanations for these numbers, ranging from declining tourism industry to the country’s ban of chemical fertilizer to the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

While these factors have each undoubtedly contributed to the economic crisis, there remains a key component almost conveniently overlooked by many economists: the monetization of Sri Lanka’s debt, an economic policy heavily favored by advocates of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

MMT argues that the federal government can spend as much money as necessary to achieve full employment without being constrained by tax revenue or debt issuance. Rather, the government can finance such spending by borrowing money from the central bank, essentially printing new money into existence in the process known as debt monetization.

Advocates of MMT argue that as long as the economy is below full employment, this tactic of debt monetization will not trigger inflation. Sri Lanka, however, serves to disprove this rather empty belief. Despite its economic crisis being defined by a critical deficiency of basic needs, such a catastrophe can be traced back to years of inflation under MMT-guided policies.

Particularly, the adoption of MMT in Sri Lanka triggered rampant inflation which, in turn, triggered a currency crisis that prevented the developing economy from importing its most crucial necessities. It’s important, however, to see this process play out over time.

Sri Lanka and the Attempt at MMT

On the eve of December 2019, Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa introduced an unprecedented series of tax cuts that saw a 33.5 percent decline in registered taxpayers, not only vastly reducing government revenue but downgrading the country’s credit rating in its ability to pay off outstanding debt.

As a result, the central bank under Governor W.D. Lakshman embarked on a campaign to increase the proportion of domestic debt through the central bank’s takeover of much of the debt’s financing, arguing that, “domestic currency debt… in a country with sovereign powers of money printing, as the modern monetary theorists would argue, is not a huge problem.” Economist Mihir Sharma in writing for Bloomberg identifies that with this statement, “Sri Lanka is the first country in the world to reference MMT officially as a justification for money printing.”

With MMT as official policy, Sharma finds a 42 percent increase in Sri Lanka’s money supply between December 2019 and August 2021. This reflects the findings of Prof. Sirimevan Colombage of the Open University of Sri Lanka, who observed a 156 percent increase in Bond Currency Derivatives (the Sri Lankan equivalent of Treasury Securities) bought by the central bank in 2021 alone, equivalent to $6.5 billion.

Contrary to MMT advocates’ predictions, however, high money supply growth brought with it a high rate of inflation. Whereas 2019 saw a rate of 3.5 percent, inflation immediately jumped to 5.7 percent in January 2020 then to an unprecedented 17.5 percent in February 2022.

It’s important to recall that this rise in inflation was not in itself the defining issue of Sri Lanka’s economic crisis, but rather a catalyst of it. Nonetheless, the fivefold increase in inflation over a roughly three-year span meant a spiraling cost of living while economic growth stagnated from the erosion of price signals.

Inflation and the Currency Crisis

MMT and its corollary of inflation still spell out a much worse scenario for developing countries that rely on imports for much of their economic activity, like Sri Lanka. The small island nation, like many other developing economies, runs a sizable trade deficit, heavily relying on the importation of everything from food and medicine to oil and machinery.

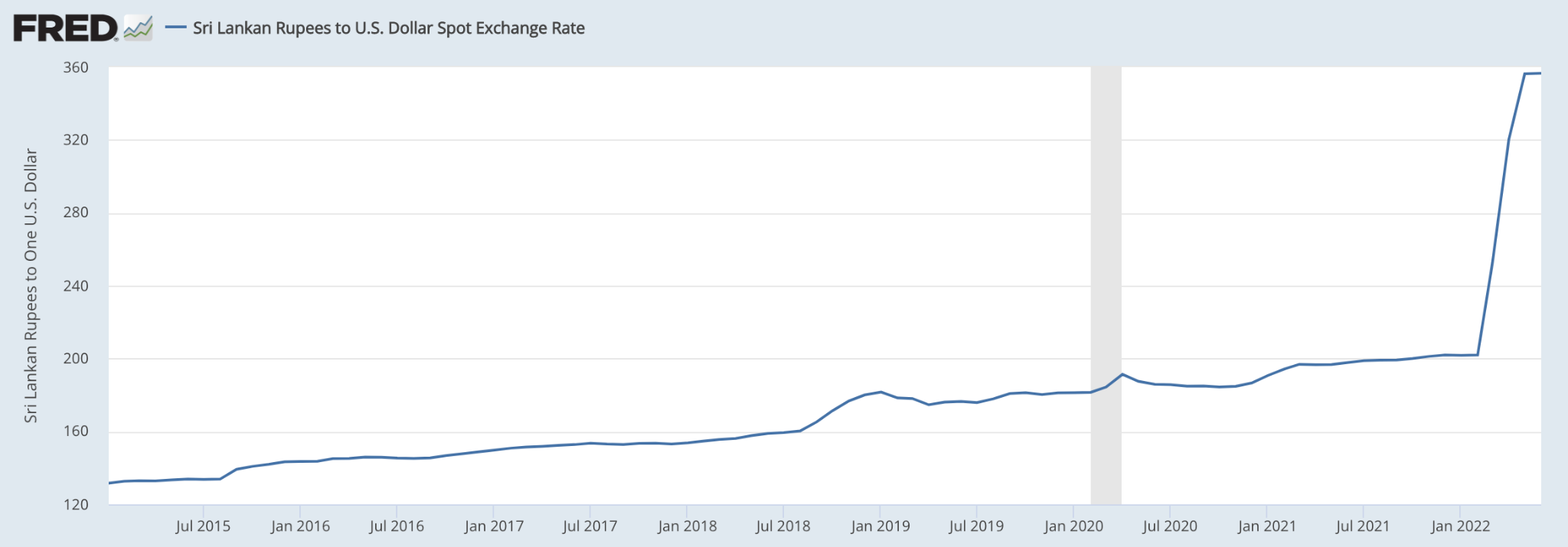

This matters because most countries finance their imports with a global reserve currency such as the US Dollar, meaning that in order to sustain its imports Sri Lanka has to first swap its own currency, the Rupee, for other currencies like the dollar. Yet as the rupee has encountered serious inflation through years of MMT policy, it’s steadily depreciated relative to the dollar before crashing in March.

Since December 2019, the cost of a US Dollar, in terms of Sri Lankan Rupees, has nearly doubled. And since imports to Sri Lanka have to be financed with a global reserve currency like the dollar, this means that imports have essentially become almost twice as expensive. Meanwhile, the collapsing rupee has made it far more expensive to buy or borrow dollars on the foreign exchange market, while the country’s trade deficit means that Sri Lanka can’t generate enough funds through exports.

The result is a dire situation of economic and social collapse in the nation. Drivers have had to wait in line for days for rationed gas. The supply of life-saving medicine has become incredibly scarce, and for some drugs, completely depleted. At the same time, chronic shortages have left millions in a state of food insecurity.

A Lesson to be Learned

Although a somber tale that will continue to take a toll on the country for months to come, the economic crisis in Sri Lanka should serve as a lesson for all other countries contemplating the lure of Modern Monetary Theory. Not only does debt monetization and seemingly limitless spending bring with it drastic inflation, but potentially economic collapse when a country can no longer afford to import the goods it’s reliant upon.

Rather, it goes back to the old adage that if something seems too good to be true, it probably is. MMT, with its promise of reaching full employment through merely printing money, has proved itself to be nothing short of a failure in its first application in Sri Lanka. Whether other countries can understand this in light of the ideology’s seductive appeal remains to be seen.

*****

This article was published by FEE, Foundation for Economic Education, and is reproduced with permission.